Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Recommendations

All Age Groups

- All persons without contraindications who are at least 6 months of age should receive annual vaccination with influenza vaccine.

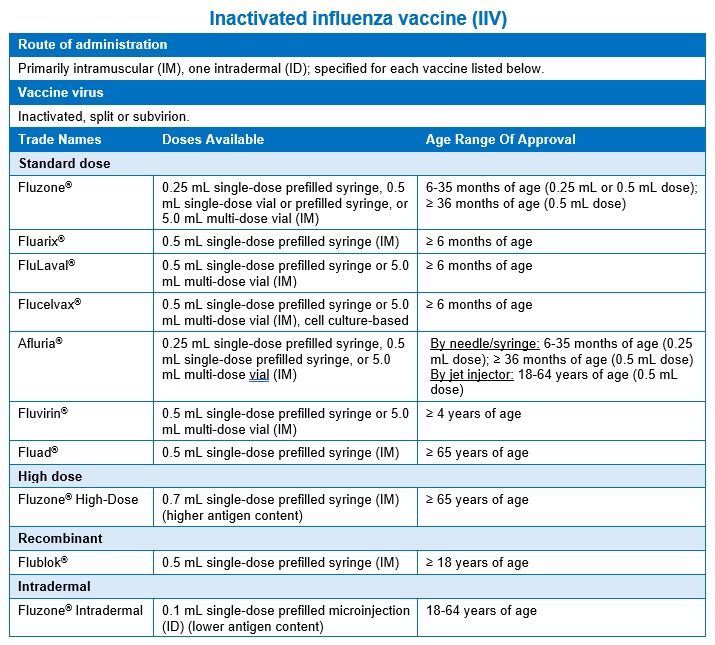

- Inactivated influenza vaccine (abbreviation: IIV; trade names: see the table on the following pages) is recommended for all age groups and during pregnancy.

- Live attenuated influenza vaccine (abbreviation: LAIV; trade name: FluMist®) is also an option for non-pregnant persons between 2 and 49 years of age 1.

- Influenza vaccine should be given as soon as it becomes available (usually between August and October in the U.S.) in order to ensure the highest possible level of protection before rates of transmission increase. Peak transmission season is usually between December and March in the United States 2-4.

- People at least 65 years of age should receive a high-dose inactivated influenza vaccine, adjuvanted inactivated influenza vaccine, or recombinant influenza vaccine, instead of the standard-dose unadjuvanted, inactivated vaccine Flucelvax 1.

Infants and Children

- Children less than 9 years of age receiving IIV for the first time ever should receive two doses at least one month apart; otherwise, one dose per year is sufficient 1.

For More Information

- ACIP Recommendations

- Vaccine Information Statements

- Live, Intranasal Influenza: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/current-vis/influenza-live-intranasal.html

- Inactivated Influenza: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/current-vis/influenza-inactivated.html

- Immunization Schedules: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-schedules/index.html

Important Information for Obstetric Providers

- Inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV) is routinely recommended during pregnancy.

- Live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) is contraindicated during pregnancy.

Disease

Influenza is caused by RNA viruses of three types. Type A influenza is the cause of most human illness and has many subtypes based on the variations in the surface antigens (i.e., hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N)), such as H1N1 or H3N2. Type B influenza also infects humans but generally causes milder illness. Type C only very rarely causes human disease.

The surface antigens on influenza viruses are always evolving, faster than most other viruses that cause human disease. This continuous stream of minor mutations is called antigenic drift and is what makes influenza so adept at evading immunity induced by prior infection or vaccination. In most years, at least some of the circulating influenza strains have drifted compared to prior years, thus even those who were infected or vaccinated in years prior may develop influenza disease again.

Occasionally a major change in one or both surface antigens occurs, known as antigenic shift; the majority of the population is usually susceptible to the new virus. The new strains generated in this manner, such as the 2009 influenza A H1N1, have the potential to cause a worldwide pandemic 2.

The incubation period for influenza is generally 2 days. The major clinical symptoms typically last a median of 4 days without treatment and include sore throat, fever, headache, myalgia, and nonproductive cough. Pneumonia is the most common complication of influenza. Other complications include Reye syndrome and myocarditis 2,5.

Pregnant individuals, young children, elderly adults, and persons with pre-existing medical conditions are at increased risk of complications and hospitalizations from influenza 6-8. There was an average of 113 annual pediatric deaths from influenza in the United States between 2010 and 2016, and about half of these were in children with no preexisting medical condition 9.

The CDC estimated an average of 23,607 annual influenza-associated deaths in the United States between 1976 and 2007 among all age groups, although these estimates ranged widely from year to year 10. Studies have also estimated an average of approximately 130,000 annual influenza-associated hospitalizations in the United States 7,11.

Vaccine

Two types of vaccines are available to protect against influenza: inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV) and live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV). LAIV (trade name: FluMist®) was not recommended for use during the 2016-2017 or 2017-2018 flu seasons due to problems with low effectiveness during the previous several seasons, but starting in the 2018-2019 season it became an option again for non-pregnant persons 2-49 years of age for whom it is otherwise appropriate 12. LAIV is administered intranasally using a single dose sprayer containing 0.2 mL, with about half (0.1 mL) sprayed in each nostril 2,12,13.

Although the exact strains differ year to year, trivalent vaccines contain one A/H3N2 strain, one A/H1N1 strain, and one B strain from the Victoria lineage; quadrivalent vaccines contain these same three strains plus an additional B strain from the Yamagata lineage 1,2,13,14. The 2024-2025 influenza vaccine viral composition for the U.S. will be trivalent and include: an A/Victoria/4897/2022 (H1N1)pdm09-like virus (for egg-based vaccines) or an influenza A/Wisconsin/67/2022 (H1N1)pdm09-like virus (for cell culture-based and recombinant vaccines); an influenza A/Thailand/8/2022 (H3N2)-like virus (for egg-based vaccines) or an influenza A/Massachusetts/18/2022 (H3N2)-like virus (for cell culture-based or recombinant vaccines); and an influenza B/Austria/1359417/2021 (Victoria lineage)-like virus 1.

IIVs recommended by the ACIP for use in the United States are detailed in the table below.

Vaccine Effectiveness

The effectiveness of influenza vaccines varies each year in relation to the match between the vaccine strains and the circulating strain. Effectiveness can also vary by the age and health status of the vaccine recipient 2. Effectiveness has been shown to decline significantly over the first six months post-vaccination, albeit at different rates depending on the vaccine 19-21. However, even in years when the vaccine has a lower effectiveness relative to other years, receiving the vaccine still reduces risk of infection, severe illness, hospitalization, and death due to influenza. In addition, high vaccine coverage prevents disease transmission and helps to protect those most vulnerable to serious influenza illness

Vaccine Safety

Common adverse reactions to IIV include local reactions such as soreness, erythema and induration at the injection site, which are reported at variable rates, but are usually mild and typically last no more than 2 days. Systemic symptoms such as sensation of fever, chills, malaise, and myalgia are also common. These symptoms typically begin within 6–12 hours of vaccination and usually last for only a few hours. Such symptoms are usually mild but have been reported in 4-<30% of children receiving IIV 23-29. Myalgia within a week of vaccination has been reported among 14-16% of adults receiving unadjuvanted IIV and 31-39% of adults receiving adjuvanted IIV 30, with even higher rates among recipients of the 2009 pandemic H1N1 vaccine 31.

Rarely, allergic reactions such as hives, angioedema, allergic asthma, or systemic anaphylaxis occur after vaccination, probably due to hypersensitivity to a vaccine component. See the Do Vaccines Cause Hypersensitivity Reactions? summary for more details.

Influenza vaccination has been associated with a very small increased risk of GBS in adults, leading to about 1-3 excess cases of GBS per million persons vaccinated. This is much less than the estimated risk after wild-type influenza infection, providing further evidence that the benefits of influenza vaccination greatly outweigh the risks.32,33 See the Do Vaccines Cause Guillain-Barré Syndrome? summary for more details.

IIV cannot cause influenza, as all viruses contained in the vaccine are inactivated and noninfectious.34 LAIV also cannot cause influenza as it is made from weakened flu virus.34

Contraindications and Precautions

An important contraindication for IIV and LAIV is having had a severe allergic reaction (e.g. anaphylaxis) to a vaccine component or previous vaccination. However, this does not include egg allergies, even though most influenza vaccines are grown in embryonated chicken eggs (exceptions being the recombinant vaccine Flublok® and the cell culture-based Flucelvax®, which are egg-free) 1. This is because the vaccines marketed in the United States have been found to contain extremely small amounts or undetectable amounts of egg protein and studies have indicated that egg allergic patients can safely receive influenza vaccines 15,16. The ACIP recommends that those with a history of egg allergy receive any licensed, recommended influenza vaccine that is otherwise appropriate; as all vaccinations should be supervised by a health care provider who is able to recognize and manage severe allergic reactions such as anaphylaxis 1. The American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology (AAAAI) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) do not recommend any additional special precaution because there does not appear to be any increased risk of severe allergic reactions to these vaccines in persons with egg allergy 17,18.

Other contraindications for LAIV include: pregnancy; children and adolescents receiving concomitant aspirin- or salicylate-containing medications; children 2-4 years old who have received a diagnosis of asthma or have had an asthma or wheezing episode within the last 12 months; immunocompromised persons; those who are close contacts or caregivers of severely immunosuppressed persons requiring a protected environment; persons with cranial CSF leaks; persons with cochlear implants; persons receiving influenza antiviral medication (within the previous 48 hours for oseltamivir and zanamivir, previous 5 days for peramivir, and previous 17 days for baloxavir).1,14

Precautions to IIV and LAIV include moderate to severe acute illness with or without fever, as well as a diagnosis of Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) within 6 weeks after a previous dose of influenza vaccine. Other precautions to LAIV include children under 5 years old with asthma, as well as persons with any underlying medical condition other than those already contraindicated which might predispose to complications after infection with wild-type influenza virus.1,14

The complete current recommendations of the ACIP regarding influenza vaccine delivery can be found at the following website: https://www.cdc.gov/acip-recs/hcp/vaccine-specific/flu.html

Considerations in Pregnancy

Pregnant individuals may receive any licensed, recommended, age-appropriate IIV. LAIV is contraindicated during pregnancy.2,12,13,36,37

Pregnant individuals and young children are at increased risk of complications and hospitalizations from influenza. Infection with influenza during pregnancy has been associated with an increased risk of adverse outcomes to the mother including respiratory hospitalization, pneumonia, adult respiratory distress syndrome, overwhelming sepsis and death.6 A CDC study estimated that 12% of all pregnancy-related deaths during the 2009-2010 pandemic season were attributed to confirmed or possible infection with pandemic influenza.38

IIV was shown to reduce non-specific febrile respiratory illness in pregnant individuals by over one third. Vaccine effectiveness was most pronounced during influenza season. Vaccination in pregnancy is beneficial not just for the mother, but for her unborn child as well. Maternal influenza vaccination was shown in one study to reduce proven influenza illness in infants under 6 months of age by up to 63% 39. In several other studies, IIV was shown to reduce the risk of low birthweight and premature birth 40,41. Some studies have found that pregnant individuals who received influenza vaccine had a lower likelihood of stillbirth than those who did not,42-44 although the evidence for this is inconsistent and has methodological limitations.44-46

A large body of evidence demonstrates the safety of IIV for both pregnant individuals and their unborn children.47-55 Concomitant administration of Tdap and influenza vaccines during pregnancy is not associated with a higher risk of adverse outcomes compared to sequential vaccination.56 In a 2017 publication, Donahue et al. reported results from a case-control study examining the risk of spontaneous abortion (SAb) following receipt of inactivated influenza vaccines containing A/H1N1pdm2009 antigen in the 2010-11 and 2011-12 seasons.57 The study found an association between influenza vaccine and SAb, particularly among women who had received pandemic H1N1 vaccine in the previous year as well.57 However, a subsequent case-control study from Donahue et al., matched on three age groups and with a population three times the size of the previous study, revealed no significant association between influenza vaccine receipt and SAb, regardless of prior season vaccination status.58 One randomized trial recruiting women at 17-34 weeks gestation,59 fourteen observational studies,58,60-72 two systematic reviews,51,73 and one meta-analysis42 have assessed a potential association between influenza vaccine and SAb or a related outcome, and none have found an association. See the Do Vaccines Cause Spontaneous Abortion? summary for more details.

References

1. Grohskopf LA, Blanton LH, Ferdinands JM, Chung JR, Broder KR, Talbot HK. Prevention and Control of Seasonal Influenza with Vaccines: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices — United States, 2023–24 Influenza Season. MMWR Recommendations and reports : Morbidity and mortality weekly report Recommendations and reports. 2023;RR(2):1–25.

2. Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases. Washington D.C.: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2015.

3. Britton A, Roper LE, Kotton CN, et al. Use of Respiratory Syncytial Virus Vaccines in Adults Aged ≥60 Years: Updated Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices – United States, 2024. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2024;73(32):696-702.

4. Panagiotakopoulos L, Godfrey M, Moulia DL, et al. Use of an Additional Updated 2023-2024 COVID-19 Vaccine Dose for Adults Aged ≥65 Years: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices – United States, 2024. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2024;73(16):377-381.

5. Fry AM, Goswami D, Nahar K, et al. Efficacy of oseltamivir treatment started within 5 days of symptom onset to reduce influenza illness duration and virus shedding in an urban setting in Bangladesh: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet Infectious diseases. 2014;14(2):109-118.

6. Tamma PD, Steinhoff MC, Omer SB. Influenza infection and vaccination in pregnant women. Expert review of respiratory medicine. 2010;4(3):321-328.

7. Kostova D, Reed C, Finelli L, et al. Influenza Illness and Hospitalizations Averted by Influenza Vaccination in the United States, 2005-2011. PloS one. 2013;8(6):e66312.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. People at High Risk of Developing Flu–Related Complications. 2018; https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/disease/high_risk.htm. Accessed March, 2018.

9. Shang M, Blanton L, Brammer L, Olsen SJ, Fry AM. Influenza-Associated Pediatric Deaths in the United States, 2010–2016. Pediatrics. 2018.

10. Estimates of deaths associated with seasonal influenza — United States, 1976-2007. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2010;59(33):1057-1062.

11. Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E, et al. Influenza-associated hospitalizations in the United States. Jama. 2004;292(11):1333-1340.

12. Grohskopf LA, Sokolow LZ, Fry AM, Walter EB, Jernigan DB. Update: ACIP Recommendations for the Use of Quadrivalent Live Attenuated Influenza Vaccine (LAIV4) – United States, 2018-19 Influenza Season. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2018;67(22):643-645.

13. Grohskopf LA, Alyanak E, Broder KR, et al. Prevention and Control of Seasonal Influenza with Vaccines: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices – United States, 2020-21 Influenza Season. MMWR Recommendations and reports : Morbidity and mortality weekly report Recommendations and reports. 2020;69(8):1-24.

14. Grohskopf LA, Blanton LH, Ferdinands JM, et al. Prevention and Control of Seasonal Influenza with Vaccines: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices – United States, 2022-23 Influenza Season. MMWR Recommendations and reports : Morbidity and mortality weekly report Recommendations and reports. 2022;71(1):1-28.

15. Greenhawt MJ, Spergel JM, Rank MA, et al. Safe administration of the seasonal trivalent influenza vaccine to children with severe egg allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012;109(6):426-430.

16. Greenhawt M, Turner PJ, Kelso JM. Administration of influenza vaccines to egg allergic recipients: A practice parameter update 2017. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology.120(1):49-52.

17. American Academy of Allergy Asthma and Immunology. Egg Allergy and the Flu Vaccine. https://www.aaaai.org/conditions-and-treatments/library/allergy-library/egg-allergy-and-the-flu-vaccine. Accessed March, 2018.

18. Dreskin SC, Halsey NA, Kelso JM, et al. International Consensus (ICON): allergic reactions to vaccines. The World Allergy Organization journal. 2016;9(1):32.

19. Young B, Sadarangani S, Jiang L, Wilder-Smith A, Chen MI. Duration of Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness: A Systematic Review, Meta-analysis, and Meta-regression of Test-Negative Design Case-Control Studies. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2018;217(5):731-741.

20. Clements ML, Betts RF, Tierney EL, Murphy BR. Resistance of adults to challenge with influenza A wild-type virus after receiving live or inactivated virus vaccine. Journal of clinical microbiology. 1986;23(1):73-76.

21. Belshe RB, Edwards KM, Vesikari T, et al. Live attenuated versus inactivated influenza vaccine in infants and young children. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(7):685-696.

22. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccine Effectiveness – How Well Does the Flu Vaccine Work? 2017; https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/qa/vaccineeffect.htm. Accessed March, 2018.

23. Brady RC, Hu W, Houchin VG, et al. Randomized trial to compare the safety and immunogenicity of CSL Limited’s 2009 trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine to an established vaccine in United States children. Vaccine. 2014;32(52):7141-7147.

24. Greenberg DP, Robertson CA, Landolfi VA, Bhaumik A, Senders SD, Decker MD. Safety and immunogenicity of an inactivated quadrivalent influenza vaccine in children 6 months through 8 years of age. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 2014;33(6):630-636.

25. Baxter R, Jeanfreau R, Block SL, et al. A Phase III evaluation of immunogenicity and safety of two trivalent inactivated seasonal influenza vaccines in US children. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 2010;29(10):924-930.

26. Nolan T, Richmond PC, McVernon J, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of an inactivated thimerosal-free influenza vaccine in infants and children. Influenza and other respiratory viruses. 2009;3(6):315-325.

27. Domachowske JB, Pankow-Culot H, Bautista M, et al. A randomized trial of candidate inactivated quadrivalent influenza vaccine versus trivalent influenza vaccines in children aged 3-17 years. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2013;207(12):1878-1887.

28. Langley JM, Carmona Martinez A, Chatterjee A, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of an inactivated quadrivalent influenza vaccine candidate: a phase III randomized controlled trial in children. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2013;208(4):544-553.

29. Tregnaghi MW, Stamboulian D, Vanadia PC, et al. Immunogenicity, safety, and tolerability of two trivalent subunit inactivated influenza vaccines: a phase III, observer-blind, randomized, controlled multicenter study. Viral immunology. 2012;25(3):216-225.

30. Beran J, Peeters M, Dewe W, Raupachova J, Hobzova L, Devaster JM. Immunogenicity and safety of quadrivalent versus trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine: a randomized, controlled trial in adults. BMC infectious diseases. 2013;13:224.

31. Nicholson KG, Abrams KR, Batham S, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of a two-dose schedule of whole-virion and AS03A-adjuvanted 2009 influenza A (H1N1) vaccines: a randomised, multicentre, age-stratified, head-to-head trial. The Lancet Infectious diseases. 2011;11(2):91-101.

32. Vellozzi C, Iqbal S, Broder K. Guillain-Barre syndrome, influenza, and influenza vaccination: the epidemiologic evidence. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2014;58(8):1149-1155.

33. Salmon DA, Proschan M, Forshee R, et al. Association between Guillain-Barre syndrome and influenza A (H1N1) 2009 monovalent inactivated vaccines in the USA: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2013;381(9876):1461-1468.

34. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Misconceptions about Seasonal Flu and Flu Vaccines. 2017; https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/qa/misconceptions.htm. Accessed March, 2018.

35. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccine Information Statement – Live Attenuated Influenza Vaccine. In:2015.

36. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 741: Maternal Immunization. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2018;131(6):e214-e217.

37. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 732: Influenza Vaccination During Pregnancy. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2018;131(4):e109-e114.

38. Callaghan WM, Creanga AA, Jamieson DJ. Pregnancy-Related Mortality Resulting From Influenza in the United States During the 2009-2010 Pandemic. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2015;126(3):486-490.

39. Zaman K, Roy E, Arifeen SE, et al. Effectiveness of maternal influenza immunization in mothers and infants. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(15):1555-1564.

40. Rasmussen SA, Jamieson DJ, Uyeki TM. Effects of influenza on pregnant women and infants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207(3 Suppl):S3-8.

41. Phadke VK, Omer SB. Maternal vaccination for the prevention of influenza: current status and hopes for the future. Expert review of vaccines. 2016;15(10):1255-1280.

42. Bratton KN, Wardle MT, Orenstein WA, Omer SB. Maternal influenza immunization and birth outcomes of stillbirth and spontaneous abortion: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2015;60(5):e11-19.

43. Regan AK, Moore HC, de Klerk N, et al. Seasonal Trivalent Influenza Vaccination During Pregnancy and the Incidence of Stillbirth: Population-Based Retrospective Cohort Study. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2016;62(10):1221-1227.

44. Fell DB, Platt RW, Lanes A, et al. Fetal death and preterm birth associated with maternal influenza vaccination: systematic review. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2015;122(1):17-26.

45. Fell DB, Bhutta ZA, Hutcheon JA, et al. Report of the WHO technical consultation on the effect of maternal influenza and influenza vaccination on the developing fetus: Montreal, Canada, September 30-October 1, 2015. Vaccine. 2017;35(18):2279-2287.

46. Savitz DA, Fell DB, Ortiz JR, Bhat N. Does influenza vaccination improve pregnancy outcome? Methodological issues and research needs. Vaccine. 2015;33(47):6430-6435.

47. Tamma PD, Ault KA, del Rio C, Steinhoff MC, Halsey NA, Omer SB. Safety of influenza vaccination during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201(6):547-552.

48. Bednarczyk RA, Adjaye-Gbewonyo D, Omer SB. Safety of influenza immunization during pregnancy for the fetus and the neonate. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207(3 Suppl):S38-46.

49. Keller-Stanislawski B, Englund JA, Kang G, et al. Safety of immunization during pregnancy: a review of the evidence of selected inactivated and live attenuated vaccines. Vaccine. 2014;32(52):7057-7064.

50. Vaccines against influenza WHO position paper – November 2012. Releve epidemiologique hebdomadaire. 2012;87(47):461-476.

51. McMillan M, Porritt K, Kralik D, Costi L, Marshall H. Influenza vaccination during pregnancy: A systematic review of fetal death, spontaneous abortion, and congenital malformation safety outcomes. Vaccine. 2015;33(18):2108-2117.

52. Polyzos KA, Konstantelias AA, Pitsa CE, Falagas ME. Maternal Influenza Vaccination and Risk for Congenital Malformations: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2015;126(5):1075-1084.

53. Kharbanda EO, Vazquez-Benitez G, Lipkind H, Naleway A, Lee G, Nordin JD. Inactivated influenza vaccine during pregnancy and risks for adverse obstetric events. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2013;122(3):659-667.

54. Fabiani M, Bella A, Rota MC, et al. A/H1N1 pandemic influenza vaccination: A retrospective evaluation of adverse maternal, fetal and neonatal outcomes in a cohort of pregnant women in Italy. Vaccine. 2015;33(19):2240-2247.

55. Ludvigsson JF, Strom P, Lundholm C, et al. Risk for Congenital Malformation With H1N1 Influenza Vaccine: A Cohort Study With Sibling Analysis. Annals of internal medicine. 2016;165(12):848-855.

56. Sukumaran L, McCarthy NL, Kharbanda EO, et al. Safety of Tetanus Toxoid, Reduced Diphtheria Toxoid, and Acellular Pertussis and Influenza Vaccinations in Pregnancy. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2015;126(5):1069-1074.

57. Donahue JG, Kieke BA, King JP, et al. Association of spontaneous abortion with receipt of inactivated influenza vaccine containing H1N1pdm09 in 2010–11 and 2011–12. Vaccine. 2017;35(40):5314-5322.

58. Donahue JG, Kieke BA, King JP, et al. Inactivated influenza vaccine and spontaneous abortion in the Vaccine Safety Datalink in 2012-13, 2013-14, and 2014-15. Vaccine. 2019;37(44):6673-6681.

59. Steinhoff MC, Katz J, Englund JA, et al. Year-round influenza immunisation during pregnancy in Nepal: a phase 4, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet Infectious diseases. 2017;17(9):981-989.

60. Chambers CD, Johnson D, Xu R, et al. Risks and safety of pandemic H1N1 influenza vaccine in pregnancy: birth defects, spontaneous abortion, preterm delivery, and small for gestational age infants. Vaccine. 2013;31(44):5026-5032.

61. Chambers CD, Johnson DL, Xu R, et al. Safety of the 2010–11, 2011–12, 2012–13, and 2013–14 seasonal influenza vaccines in pregnancy: Birth defects, spontaneous abortion, preterm delivery, and small for gestational age infants, a study from the cohort arm of VAMPSS. Vaccine. 2016;34(37):4443-4449.

62. Chavant F, Ingrand I, Jonville-Bera A, et al. The PREGVAXGRIP Study: a Cohort Study to Assess Foetal and Neonatal Consequences of In Utero Exposure to Vaccination Against A(H1N1)v2009 Influenza. Drug Safety. 2013;36(6):455-465.

63. Huang WT, Tang FW, Yang SE, Chih YC, Chuang JH. Safety of inactivated monovalent pandemic (H1N1) 2009 vaccination during pregnancy: a population-based study in Taiwan. Vaccine. 2014;32(48):6463-6468.

64. Ludvigsson JF, Strom P, Lundholm C, et al. Maternal vaccination against H1N1 influenza and offspring mortality: population based cohort study and sibling design. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2015;351:h5585.

65. Ma F, Zhang L, Jiang R, et al. Prospective cohort study of the safety of an influenza A(H1N1) vaccine in pregnant Chinese women. Clinical and vaccine immunology : CVI. 2014;21(9):1282-1287.

66. Oppermann M, Fritzsche J, Weber-Schoendorfer C, et al. A(H1N1)v2009: A controlled observational prospective cohort study on vaccine safety in pregnancy. Vaccine. 2012;30(30):4445-4452.

67. Pasternak B, Svanström H, Mølgaard-Nielsen D, et al. Vaccination against pandemic A/H1N1 2009 influenza in pregnancy and risk of fetal death: cohort study in Denmark. BMJ : British Medical Journal. 2012;344.

68. Tavares F, Nazareth I, Monegal JS, Kolte I, Verstraeten T, Bauchau V. Pregnancy and safety outcomes in women vaccinated with an AS03-adjuvanted split virion H1N1 (2009) pandemic influenza vaccine during pregnancy: A prospective cohort study. Vaccine. 2011;29(37):6358-6365.

69. Irving SA, Kieke BA, Donahue JG, et al. Trivalent Inactivated Influenza Vaccine and Spontaneous Abortion. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2013;121(1):159-165.

70. Sammon CJ, Snowball J, McGrogan A, de Vries CS. Evaluating the hazard of foetal death following H1N1 influenza vaccination; a population based cohort study in the UK GPRD. PloS one. 2012;7(12):e51734.

71. Heikkinen T, Young J, van Beek E, et al. Safety of MF59-adjuvanted A/H1N1 influenza vaccine in pregnancy: a comparative cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207(3):177.e171-178.

72. de Vries L, van Hunsel F, Cuppers-Maarschalkerweerd B, van Puijenbroek E, van Grootheest K. Adjuvanted A/H1N1 (2009) influenza vaccination during pregnancy: description of a prospective cohort and spontaneously reported pregnancy-related adverse reactions in the Netherlands. Birth defects research Part A, Clinical and molecular teratology. 2014;100(10):731-738.

73. Bednarczyk RA, Adjaye-Gbewonyo D, Omer SB. Safety of influenza immunization during pregnancy for the fetus and the neonate. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2012;207(3):S38-S46.